“Everyone’s in Love, but Nobody’s Horny”

New essay in Reactor Magazine!

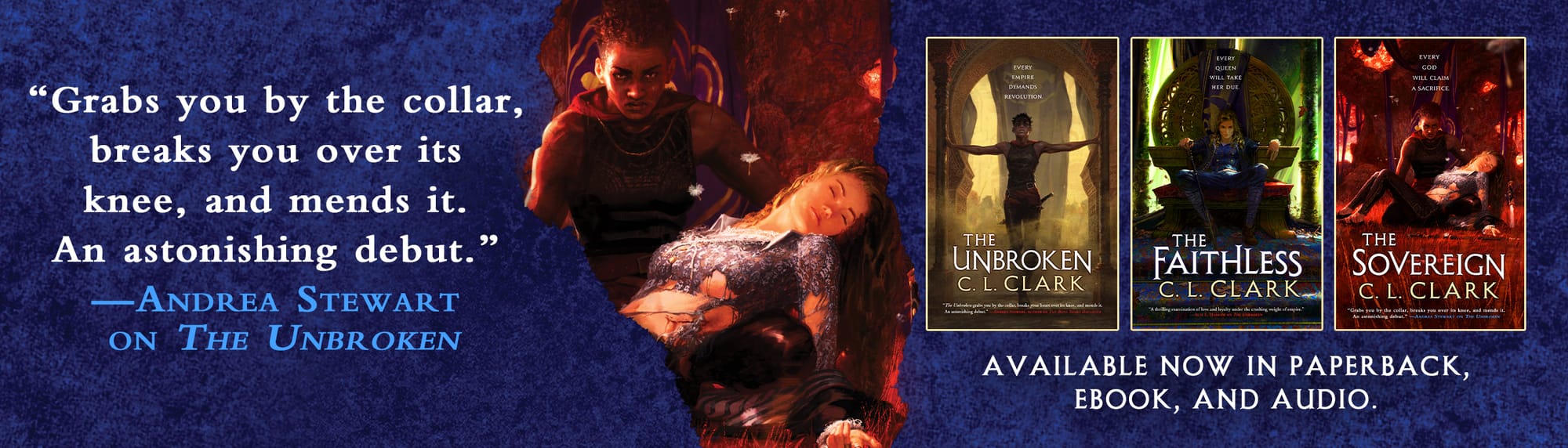

It’s a bumping week for C. L. Clark publications! In addition to The Sovereign and Fate’s Bane dropping on Sept 30, Reactor also dropped the essay I wrote about sex—“Everyone’s in Love, but Nobody’s Horny.”

One of the things that fascinates me in literary discourse is what we deem acceptable and unacceptable in books, and what’s considered extraneous. Very often, one can see how desire is more frowned upon than gruesome violence.

As a young reader, one just figuring out their sexuality, I found myself ravenous for any queer sex scene—yeah, because it was hot, sure, but because I was yearned to see people like me so that I could learn how to be…well, like me.

One of the many reasons I continue to write sex in my books—not just “boot scenes”1 but full, explicit scenes is because I also think that women, especially queer women, are made to hide their carnal desires, or that carnality is supposed to be something that is dirty, only for men, and bad men at that. But there are a lot of things to push back on with that and my fiction is one place I do that.

This essay is another. (I’m certain there will be many more essays, because just typing up this introduction has gotten me rarin’ to go another tangent.)

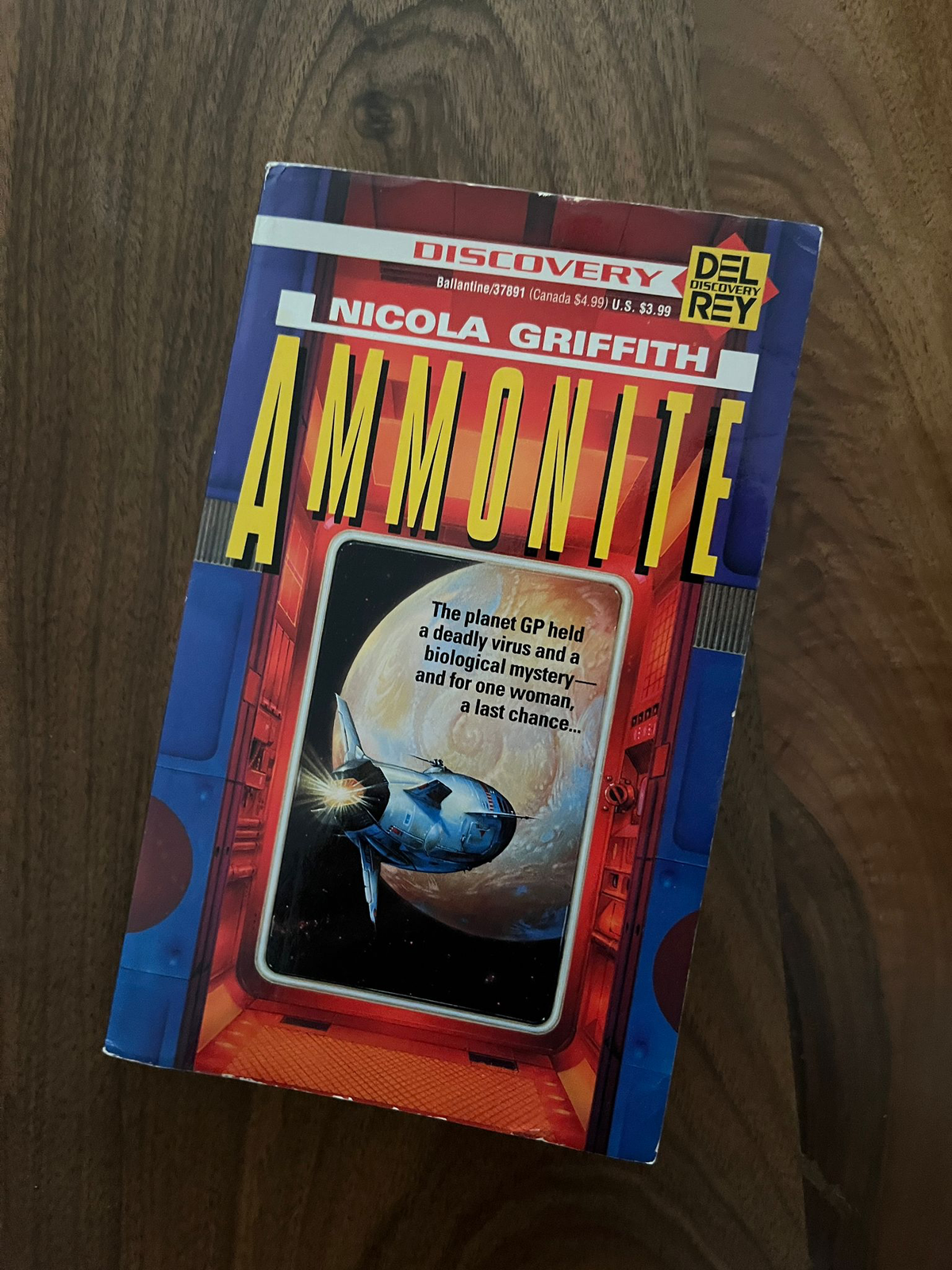

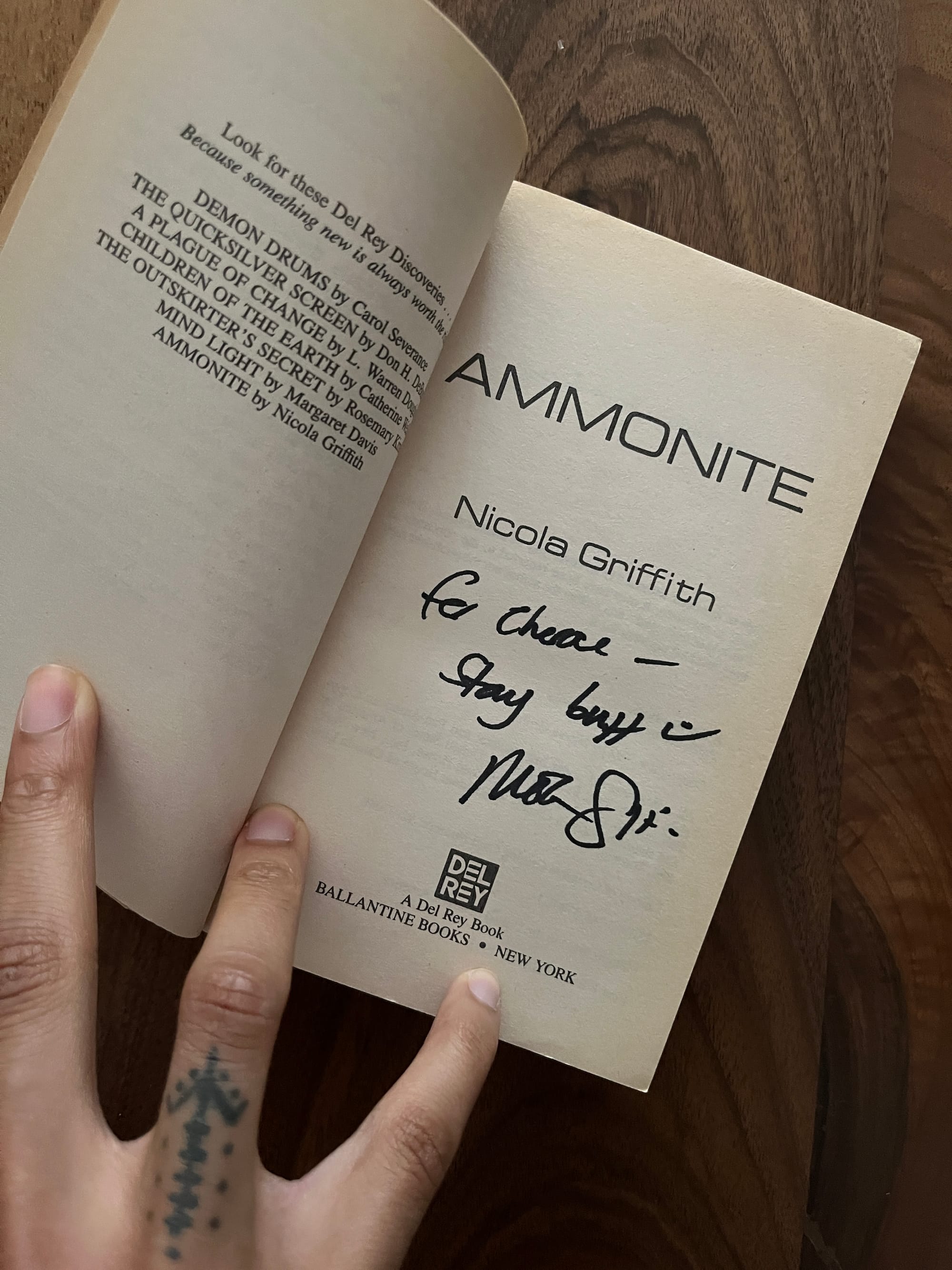

To focus on this essay: it’s an exploration of the moralization of sex in literature, and how sex is as useful a tool as any other in character and world building, via a new favorite novel—Ammonite by Nicola Griffith. I’ve mentioned it before, how it rewired me along with James Baldwin’s Another Country, which provides an opening epigraph.

From the essay:

“We are in a cultural moment that demands purity of characters, particularly characters in romantic narratives (whether the romantic storylines are primary or secondary). In book reviews, readers bemoan the “problematic,” and unequal power dynamics make them “uncomfortable.”[1] This insistence on only the most upstanding and unblemished unions erases all possibility of person-making, which is to say, growth and change. Instead, we end up with narrative corn syrup: an uncomplicated, saccharine meal that goes down fast but is, at the end of the day, unsatisfying.

There is a glorious and necessary specificity of worldbuilding and character building which requires work and attention on the part of the author to understand exactly who these characters are and how they would feel about the sex acts they do (or don’t!) participate in. The tropes of intimacy that have been joys and structural devices and genre indicators all, this “corn syrup,” serve to lull us authors into neutralizing our characters, balancing out their pH until they’re as inert as pure water. Instead of stopping at the generalization of a character’s type, we must imbue them with unique personalities driven by the specifics of their world—enough personality to be disliked by some, enough honesty to admit their desires, and enough humanity to make mistakes in the attempt to reach them.

This is partly why reading Nicola Griffith’s Ammonite recently felt like having real sustenance….”

1 I learned the term “boot scene” from the annotated copy of the Dragonlance Chronicles, where the authors said a boot scene was a sex scene where you saw the kissing perhaps, but the next thing you know, the characters are pulling their boots back on.