Does Fantasy Water Down Violent Conflict?

Is it all just a practical matter? Or is there something more?

I’m in Ireland with my family right now. They’ve come over for the book launch and so we’re doing a little side trip. I’m having a blast as a fantasy nerd, as you might imagine. I’ve been down to the Cliffs of Moher (amazing) and seen some ancient tombs and a lot of limestone and the Giant’s Causeway (I love rocks!) and the Dark Hedges (and trees!) and other Game of Thrones sites and walked across a rickety rope bridge at Carrick-a-rede—basically, living my best life.

Yesterday, we had a stop over in Belfast and we all separated to have our own little museum days and I went to the Ulster Museum to go to the Troubles and Beyond exhibit. (I’ve linked to the digital exhibition that’s free to go through if you’d like to learn more.) I was interested in learning more about Irish history, but also seeing how certain strategies and consequences might be applied in Palestine, and how it reflected the civil rights battles in the U.S. (I learned that many of the initial demonstrations in Ireland were inspired by the U.S. civil rights movement, which was cool.)

As you probably know if you’ve found me through my books or my essays, I’m very interested in the legacy of colonial struggle and what it looks from the inside, as individual people living at the mercy of signatures scrawled through your land a million miles away by people who don’t know you and certainly don’t care.

This exhibit continued to challenge my thinking in that regard, especially in how we/I write about it as a fantasy author. I was struck again by how complicated these scenarios are. There are as many different perspectives as there are individuals. As someone who strives for a certain amount of reality in portraying these conflicts in my own work, I can’t help but feel that we flatten these sorts of conflicts into simpler pieces that water down the gravity and the complexity of finding future solutions. And, since I do think that fantasy can be as educational in teaching us how to think, how to move through the world, I think that’s…well, it’s a little unfortunate.

Part of the reason this happens, I’m sure, is because of the skill it takes to create an imaginary conflict as rich and painful as the real ones we have all lived through or witnessed. It takes knowledge of conflict, and research. You have to understand and spend time within real world conflicts to understand the breadth of their consequences. All of that takes time, including the time of writerly growth. Learning how to manage a narrative that encompasses all of it, from characters to setting, politics and geopolitics. Admittedly, that’s not everyone’s interest.

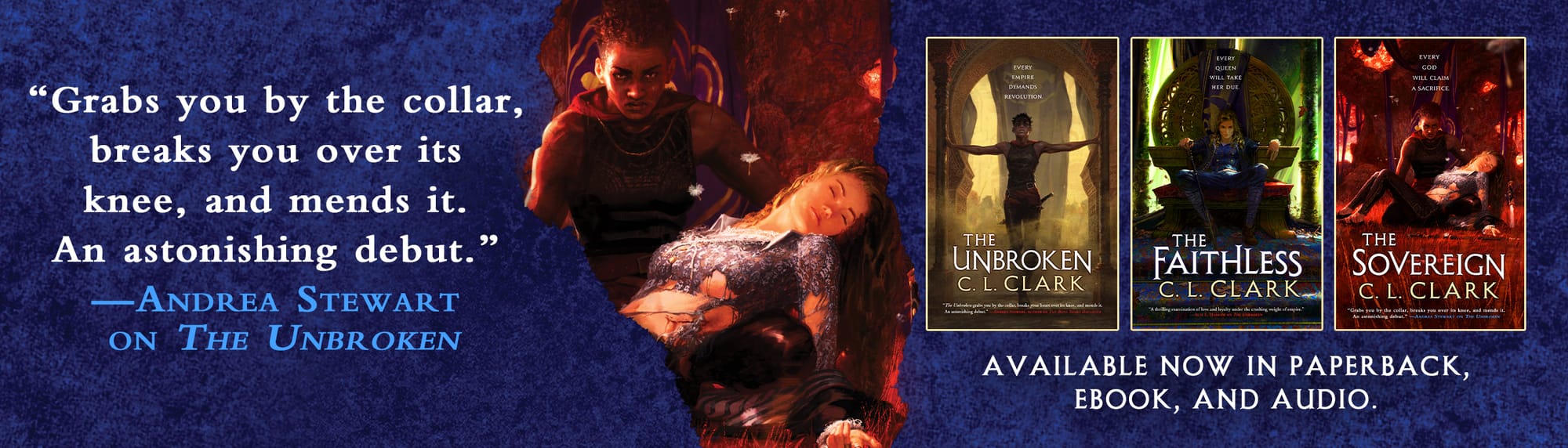

It may also be a practical choice. I have made this practical choice myself. It takes a monumental amount of effort and time for one person to keep track of all of the different factions and motivations of political conflicts. I tried to make a couple of factions within the rebels in The Unbroken but I settled with a truncated version of that, killing off any off-shoots because it would have made the book to big—too real, too complicated, bringing out new layers that I didn’t want to deal with in the scope of that book. I didn’t feel ready to tackle it as a novelist, or as a student of history.

How much of that pruning becomes the way we always deal with these kinds of conflicts? Too complicated, too big. Outside of my scope. Too real. Too much. We’ll deal with it in a sequel. A prequel. A different series.

I don’t feel like it’s always intentional, though, to have a story that leaves things out. There are plenty trying to grapple with the truth that is conflict. To hand: Rakesfall by Vajra Chadraskeera and Winged Histories by Sofia Samatar. Both of those, surprisingly, are quite slim volumes—the authors choose very deliberately what they will show and not show, while still depicting many of the perspectives of those who live through armed political struggle. They flex the storytelling strategies, force themselves into new shapes to grapple with it, using unique structures, poetry, and characters who have distinct oversight or impact on the conflict at hand. Rakesfall in particular is very experimental, reflective the cyclical aspects of conflict. More traditionally, you have epic fantasies Game of Thrones that attempt to tackle the writhing factions by taking up all the space possible, creating a sprawling narrative that requires many, many books to tell.

All of them deal with the different interests, nationalism, loyalty to crowns, rebellion, revolution. It’s just that fiction is a very inexact art—anything that truly tries to contain the world will fail a bit. And yet, somehow, each of these stories manages to contain some part of the whole truth.

We also have to acknowledge that even the history books that relate these real world conflicts have to pick and choose certain focuses, and the ones that try to do it all are massive. So maybe we just have to accept a certain amount of incompleteness. I just don’t want it to feel incomplete and false, over-simplified to the point of a lie. I don’t want the story to feel washed out without exploring the depth of the complexity in solving the problem. This was one of the struggles I faced in writing the end of the Magic of the Lost trilogy (The Sovereign).

Personally, I think it’s one of the things I have seized on, a white whale of mine to understand this, to put it into narrative. To make it sink into readers as well, the ever-rippling nature of these conflicts and of what might be needed for future reconciliation. To explore different versions of resolution in my imagination so that we might explore them in the real world, too. To explore what The End looks like. Everything isn’t solved by a well-timed execution or unifying marriage or one last battle against the dark, winner take all.

So many books stop at the conflict ‘end’ but as the exhibit showed, the Troubles ‘ended’ several times. When is an end enough for all parties? Those multiple factions come into play here. One half of a rebel party dissatisfied. Losers not holding to their end of the surrender bargain. Overpowered genocidaires reneging on a peace agreement. Walking back civil rights over time or finding new ways to get around the agreements as written.

When I wrote The Unbroken and everyone knew it was a trilogy, it was something interesting—the series didn’t end at the successful revolution. It was just beginning. I did try to keep showing some of that, but the focus in the next book was no longer on Qazāl and its post-revolution reconstruction. Might that have been the more interesting choice? Perhaps. At the time, I did not think that I was smart enough for that. I also wanted to see Touraine grapple more with her past in Balladaire, and her relationship with Luca. So maybe for these characters, that was the right choice. (I certainly would not say that Touraine’s relationship with colonialism is simple, or even straightforward.)

As for the rebuilding…perhaps for another day. Perhaps another book. Perhaps a sequel, or a prequel, or another series entirely.